Renewing Classical Hebrew

Taking Revival Seriously

From Hadesh Vol. 1, Iss. 9 - Speech

By: Ephraim S. Ayil, Philologist and Author of Identifying the Stones of Classical Hebrew A Modern Philological Approach

Four languages are fitting for the world to use,

And they are:

Greek for song,

Latin for war,

Aramaic for elegy,

Hebrew for divine speech.1

According to the narrative promoted by linguists and the Israeli government, Hebrew is the only language to have been revived. Like most claims that are pushed by Hasbara, it is wrong.

First, it must be determined what the moniker “Hebrew” refers to, a far more difficult problem than it seems. Linguistics can provide a taxonomic answer: Hebrew is a Semitic language, itself part of the larger Afroasiatic family. Linguists can also describe Hebrew in terms of its grammar, vocabulary, phonemic inventory, and other aspects. What linguistics is, as it turns out, incapable of providing is a precise definition of a language.

The most salient questions linguists deal with, as politically-charged as a question can be, is what defines a language. In the mid-century rush to achieve value-neutrality, linguistics abandoned prescription (“ought”) in favor of description (“is”). A parallel from the field of biology is illustrative: once it was realized that life is in a continual state of evolution without definitive breaks, it became impossible to define what, exactly, a species is - the aptly-named “species problem”.

The same line of thinking, at an earlier stage in the dialectic, is found in the language-dialect problem, whereby it becomes impossible to decide what the “language” is and what the “dialect” is from a value-neutral standpoint. At some point it will be argued, perhaps already, that naming a language at any given point in time (including now) necessitates an arbitrary choice, as language changes gradually from ancestor languages. Descriptivism made it impossible to delineate a language.

Therefore, to call the language I am writing in “English” is really quite an arbitrary label, you see.

This logical absurdity is the product of true value-neutrality, which is not only impossible (the choice to study one language over others is a value-decision), but incompatible with any other value-system by exclusion. In that sense, it is also ahistorical because prescription is a natural part of language evolution at least for as long as people have been recording language in writing.

Linguistics cannot answer what distinguishes a particular language such as Hebrew nor what it should look like. These questions can only be derived by recourse to the Jewish people’s preexisting value-system.

It is further necessary to justify why one would communicate in Hebrew today. We live in the age of the ascendancy of Imperial English. Should a monolingual English-speaker find himself in a city of ten thousand or more people, anywhere in the globe, he will have someone with which to speak. As with virtually every other language, Hebrew faces the existential challenge of justifying itself against English.

But communication is not the only reason why people would choose to speak or write in a particular language over another. Language is one of the primary expressions of culture. To speak or write in Hebrew instead of English is to make a cultural choice that displays a value structure which elevates something above mere communication.

To resolve these difficulties, we must appeal to pre-modern and pre-scientific thought, where values were not only tolerated but intentionally cultivated. To understand what Hebrew is, we need only ask what the truest essence of Hebrew is. In Platonic terms, what is its form?

The ideal form of a language is defined by the language as it exists in its most iconic literature. Nearly every modern language possesses a standard for “correct” (or at least “good”) language on what it believes to be the best early work. Latin has Cicero. Arabic: the Qur’an. Sanskrit: the Vedas. English: Shakespeare and the KJV. Italian: Dante. It may necessarily follow that the act of composing an authoritative text is equally an act of establishing an authoritative register.

As it concerns Hebrew, that something must be an affinity to some element of the legacy of the Israelites, whose great cultural legacy–for whom the term magnum opus is an understatement–is the Hebrew Bible. What more iconic or authoritative model could Hebrew be defined by?

The Jewish people are defined by the Hebrew Bible (traditionally called מִקְרָא, as it was the collection of texts which were appropriate to publicly read in the synagogue). The nation of Israel was created when God led us out of Egypt and revealed to us his Divine Law (תּוֺרָה). Unlike etiological myths, our ethnogenesis continually shapes our national destiny such that it is more than the origin of our nation, it forms the essential core of it.

From the sequence of Torah > Nation of Israel > Hebrew.

People look to that authoritative text as the barometer for “good” versus “bad” language. When God via the Torah created the nation of Israel, the language of the Torah–which was based on our spoken language at the time–became our national language.

I want to disabuse the reader of the notion that the language of Miqra is identical with that colloquially spoken by people. Most languages with a literary tradition distinguish between a lower colloquial register and a higher classical register. The former we may call “colloquial Hebrew” and the latter “Classical Hebrew”.

The language of the Torah was probably based on the common language of the Semitic slaves who left Egypt in the 13th century BCE. In the articulation of the Babylonian Talmud, דִּבְּרָה תּוֹרָה כִּלְשׁוֹן בְּנֵי אָדָם “the Torah speaks like the language of men”.2 The Hebrew of the rest of Miqra was largely based on this literary standard, even with the subtlest changes that scholars have excavated: neologisms, new borrowings, the subtlest of grammatical changes.3

By studying the Classical Hebrew of Miqra, we may be able to discern the standard by which all other Hebrew can be compared.

The insufficiency of descriptive linguistics to guide the development of Hebrew reflects Hume’s is–ought problem, for how language is used can never give rise to how language ought to be used. Linguistics cannot answer these questions.

Linguistic concepts may be helpful here to disassemble language into its components. Linguists speak of a language’s lexicon (the words of the language), phonology (the sounds present in that language), phonotactics (how those sounds are ordered), syntax (meaning that arises from word order), and other aspects of grammar. I will focus only on phonology, grammar, and lexicon to avoid losing my audience.

The lexicon of Classical Hebrew is primarily of inherited Semitic stock, with borrowings from several neighboring languages including Ancient Egyptian, Akkadian, Aramaic, and Hurrian. Loanwords are not objectionable per se, as they comprise an inherent part of the character of Classical Hebrew. The error is to extrapolate from the fact that Classical Hebrew contains borrowed words that any loanword is therefore acceptable. Classical Hebrew selectively borrowed foreign vocabulary, primarily to accommodate new technologies/materials and foreign cultural concepts.

As conspicuous as loanwords from some languages are, more blatant are those which are absent. Despite their might and prestige on the seas of the late-biblical Mediterranean, Greek borrowings are notably absent from the biblical text, sans the name יָוָן ‘Greece’. This is despite extensive contact between Hebrew-speaking Phoenicians and Greeks that left an indelible Semitic mark on the Greek language. While loans from more local languages were acceptable, there was something about Greek which was not.

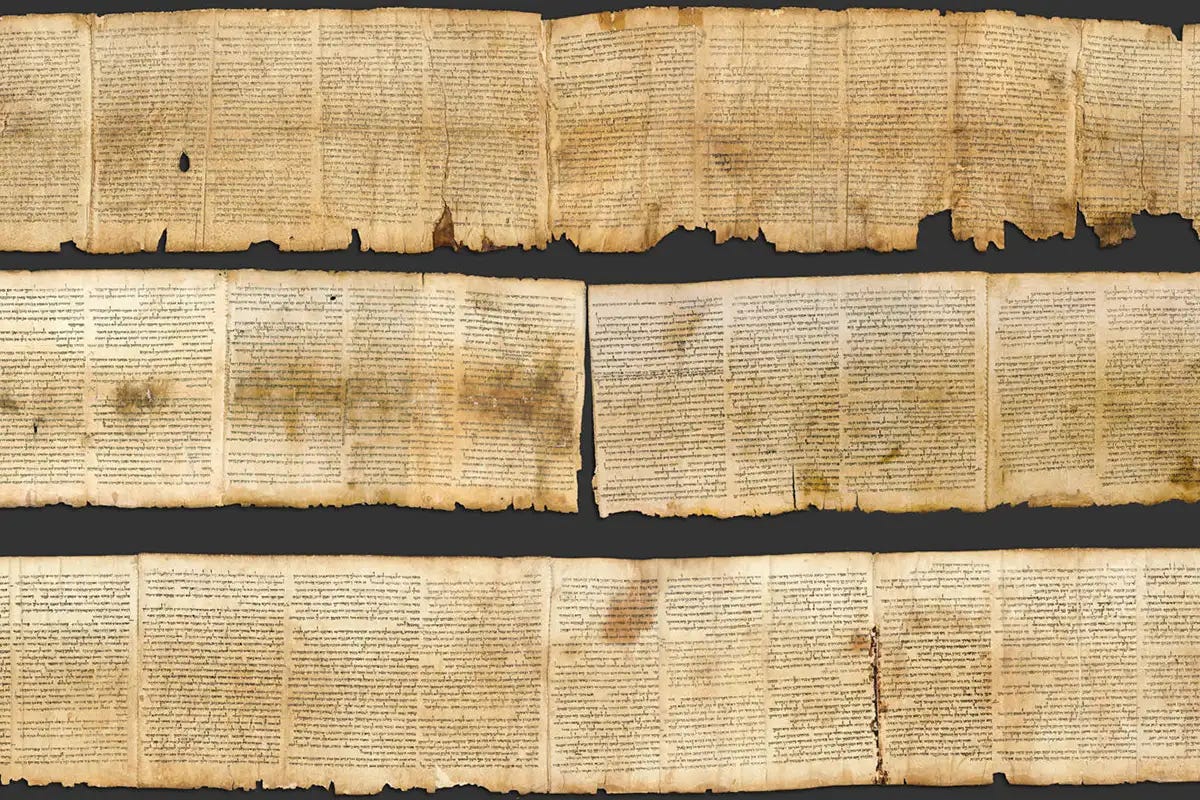

This observation holds in post-biblical texts. “There is no dispute that Greek loanwords were available to be used in Hebrew and Aramaic sources of the Hellenistic period. However, the point that emerges from Ben Sira and the Dead Sea Scrolls is that normally, literary Hebrew of the Hellenistic era avoided using Greek words”.4 The Hebrew of the Bar Kokhba letters follows suit, notable for its exceptionally pure Hebrew–even in casual correspondence. When the Sages composed the prayers and blessings in Mishnaic times, they intentionally avoided Greek and Latin loanwords.

“The prayers adopted by the rabbis represent the ultimate text in terms of the triumph of the Hebrew language. There is a recognizable Greek influence in rabbinic literature, indicating that the sages were aware of Greek and that some were proficient in the language. Nevertheless, this does not find expression in the prayers, as we find practically no Greek expressions or words in Jewish prayers.”5

If Miqra is the archetype of the Hebrew ideal, the Sages provide the model for how to compose in Classical Hebrew for all other purposes. Here again we return to the trifecta of phonology, grammar, and lexicon. The phonology of Hebrew is its most fickle aspect because it gradually changed throughout the spoken history of the language. The Sages here provide a life preserve because the correct pronunciation of Hebrew texts is legislated as a matter of halakha.6

Classical Hebrew vocabulary and grammar provide the backbone, although non-biblical vocabulary may be required to supplement the limited number of words that are actually attested within the biblical text. The existence of some Classical Hebrew words may be inferred to have existed within the language during biblical times despite their absence from the biblical text (or contemporaneous extra-biblical Hebrew texts7). For instance, the Mishna contains numerous terms absent from the Hebrew Bible, nevertheless inherited from Proto-Semitic through regular Hebrew sound changes8 (טְחוֹל ‘spleen’ from Proto-Semitic *ṭiḥāl- ‘spleen, milt’,9 גָּרוֺסָה ‘grist maker’ from Proto-Semitic *magarāśat- ‘grist maker’,10 מַשְׂרֵק ‘comb’ from Proto-Semitic *maśriḳ- ‘comb’).11

Except for proper names, loanwords from European languages including Greek and Latin would be replaced with an appropriate neologism according to classical principles. It is when the introduction of new vocabulary is concerned that the taste of the shapers of language is revealed to be either noble or destitute. The eloquence of Ciceronian thought bears an indisputable mark on every Latin text after him, Shakespeare’s mind molded English in yours all the same.

Do we have any similar figures? If my assertion that the language of the Torah (with the exception of the epic poems) reflects a new literary standard, then it is Moses no less than God that bears the primary attribution for canonizing the Hebrew language. If Moses was the first, he was certainly not the last great name. Scholars have picked up on the phenomenon of ezekielisms (neologisms coined by Yeḥezḳel)12 whereas many medieval coinages are so natural, it strains belief they are not older in provenance.

More recent figures, including Eliezer Ben Yehuda, deserve credit for many more brilliant coinages. The qualities that make for a good neologism are quite evident by comparing Ben Yehuda words with the slop that is endlessly churned out by the Academy of the Hebrew Language (which everyone seems to ignore, anyway). Ben Yehuda’s neologisms are largely according to classical principles and concise.

Israeli forms nouns/adjectives through European methods like compounding (stringing existing words together to form a new word), blending, and perhaps the most artificial of them all, acronyming. None of these methods are found in Classical Hebrew, which is solely composed of inherited vocabulary, borrowings, and innovative words (innovations) produced through the coupling of root + stem. Neologisms according to classical principles need to be constructed by combining roots and stems, or may be borrowed from an appropriate source (like Arabic, Aramaic, Persian).

True, the ancients didn’t have computers. But utilizing the components possessed by the ancients allows a new term to be created that fits perfectly within the inherited vocabulary. The new word מַחְשֵׁב is constructed from the classical root ח-שׁ-ב ‘to think, calculate’ (now naturally extended with the meaning ‘to compute’) according to the stem used to form terms for tools (like biblical מַפְתֵּחַ ‘key’ from פ-ת-ח ‘to open’). The novelty of מַחְשֵׁב is betrayed only by the fact that computers were nonexistent prior to a century ago. Thus מַחְשֵׁב may be classical even without being biblical.

A few principles may be collated for ascertaining the value of a new term, though I claim no comprehensiveness. Is the term necessary without a perfectly viable classical word? Immune from error? Borrowed from a legitimate source? A legitimate innovation? Concise? Culturally appropriate? Catechy? Homophonous or homographous with an existing classical word? Suitable for deriving new terms down the line, if necessary? Good words pass through these filters with a resounding “yes”, though the last one has more wiggle-room.

Classical Hebrew has a far richer soundscape than its modern imitator would lead one to believe. The authoritative rabbinic texts including the Mishna and two Talmuds imply (without significant elaboration) a rich phonology, with far more than twenty-two sounds for twenty-two letters.13 Her six normal plosives (b, d, g, k, p, t) are matched with six equivalent fricatives, which add up to nearly thirty-consonants. With the exception of sin and samekh, no two letters are pronounced alike.

But the obvious discrepancy between the lofty ideal we have developed and the reality of the language as is spoken by Israelis cannot be ignored.

What is “Modern Hebrew”? By its most ardent defenders, usually of the older generation, it is claimed to be a direct continuation of, indeed the modern manifestation of, the Hebrew of the Bible. Such a self-evaluation is absurd given the gross phonological, grammatic, and semantic changes which segregate the two languages.

Languages inevitably change over time, evolution is to be expected from the three-millenium gap between Biblical and Israeli Hebrew. But the change within that gap is not the standard change expected between two stages of a language. Under the influence of European languages, the phonological inventory has halved, the phonotactics are entirely different, spirants have been reanalyzed as independent phonemes, I could go on. This has forced grammatical changes, notwithstanding the radical lexical changes.

While Israelis certainly love to boast that they can “perfectly understand the Bible in its original language!”, this claim slams head-first into linguistic reality. The average Israeli student reading biblical texts is akin to a Japanese student reading ancient Chinese poetry. Although they may read a text and produce a coherent reading, they are imposing their Israeli phonological and semantic values onto the text. The reader receives a mirror of their language which they have imposed on the text instead of allowing the text to speak for itself.

In this respect, the Western student of Bible has an unmistakable advantage over their Israeli counterpart: they approach the text with significantly lessened semantic bias. It is also far easier to teach ancient sound values to a Western student with no prior familiarity towards the alphabet than an Israeli student who grew up speaking Israeli, and stubbornly imposes that system on how a word should sound.

Under the criteria considered under the Platonic ideal of the Hebrew language (phonology, lexicon, and grammar), Israeli Hebrew is completely different from Classical Hebrew.14 But is it different enough in form to be classified entirely distinctly from Hebrew, as some scholars have alleged?15

The politically-charged nature of what defines a language is all the more true when it comes to the Hebrew language, which authoritative sources like Wikipedia allege died in the fourth century CE and was mythically (in both senses of the term) resurrected by early Zionist workers. Though emotionally touching, this narrative is not true even in the loosest sense.

Hebrew died neither as a spoken language nor written language. Hebrew served as the lingua franca for European Jews of the Middle Ages, who needed to communicate across their varied spoken tongues. In the Renaissance medical schools, students were expected to be fluent speakers of Hebrew, as instruction was given in that language.

Ben Yehudah, which the common narrative attributes the credit for resurrecting Hebrew, himself claims quite the opposite—that he was inspired by the idea that Hebrew could once again be spoken by all of Israel by spending time in the Jewish communities of North Africa—where he communicated with local Jews in their only common tongue.

Yet the language spoken in Israel today is not Classical Hebrew, but a language that differs from Classical Hebrew in every respect in which a language could. Israeli phonology is half of that of Hebrew. Consequently, its phonotactics and grammar have changed by necessity. Its vocabulary is either lifted from European languages (largely English) or just as often reassigned to concepts of similar but disparate meaning from Classical Hebrew.

In a cultural environment where this new conlang pervades every aspect of culture and claims the mantle of Hebrew, the Real McCoy–Classical Hebrew–was displaced and denied its rightful place at the pinnacle of cultural prestige. The one-two-punch of Imperial English taking its rightful prestige with the imposter Israeli conlang stealing its reputation (and name, which goes by the same term in CH: שֵׁם) relegated Classical Hebrew to the margins. But these hyperconservative holdouts are largely dead now.

But I am implying a perhaps equally absurd conclusion. Am I trying to claim that the Israeli government has conspired with the entire linguistics profession to lie about the resurrection of Hebrew?

Yes.

The motives for both parties strongly incentivized maintaining this convenient fiction. For the Zionist movement, it served to legitimize the idea that theirs was a prophetically-implied project,16 as it states in Isaiah 19:18 “On that day, there shall be five cities in the land of Egypt speaking the language of Canaan (שְׂפַת כְּנַעַן)…” How could five cities in Egypt speak Hebrew if Hebrew was then-extinct? This was vague and abstract enough to not ruffle the feathers of the secular movement while allowing them to legitimize themselves to the religious.

For linguists, the mythological “resurrection of Hebrew” offered them a job program. Prior to the internet, linguistics degrees were largely useless. If someone would give you funding, you could study an ancient language or go out into the field in some obscure locale to record another dialect of something-or-another. But if language can be resurrected, then linguistics could sell their expertise in linguistic revival to affluent ethnic minorities wishing to revive their extinct tongues.

How successful linguistic revival has been is largely dependent on your definition of success, but there’s no doubt that it has been a smashing success at justifying state funding for linguists. Therefore, linguists have every incentive to keep their mouths shut about the “resurrection of Hebrew”, which makes it perhaps the most boring (and normal) conspiracy on Earth.

“Modern Hebrew” is no resurrected language. It is a zombie language, an unsettling linguistic form that on its surface, resembles the original language, but is in reality a parasite on the remains of its former self. The relationship between the real and zombie languages is that of a cheap imitation. Israeli may be sufficient to fool your average person, but to a scholar could never be confused with its true form.

This unavoidably implies a rather scandalous conclusion: rather than resurrecting Hebrew, Zionism unintentionally did what the Egyptians, Amalekites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Seleucids, Romans, Byzantines, Muslims, and Inquisitors never could. The Zionists killed Hebrew.

While conservative prudence counsels that given that linguistic revival has never been successful, it is fruitless to try, technological advances change the calculus. The ability of artificial intelligence to generate large quantities of text according to whatever standard is desired raises the possibility of tools designed to help correct bad language and teach good language.

A lexicon of Classical Biblical Hebrew must be assembled, informed by the best of modern and classical Hebrew scholarship (and with an extensive bibliography to retrace our steps). This lexicon can then be supplemented with later vocabulary as needed, avoiding the pitfalls of Israeli. For example, Miqra provides the numbers one through nine, ten, hundred, thousand, and ten thousand (myriad). The concept of zero is medieval, so the term אֶפֶס for ‘zero’ cannot be excluded. Suffice it to say, new classical terms for million, billion, and trillion must be coined.17

New and experimental pieces of software may be vibe-coded that can act as a sort of spell-correct for non-Classical vocabulary and grammar, or perhaps automatic translation tools. The democratization of the software-creation process renders this a problem of time and will, not funding. Classical texts such as those by Rav Sa`adya Ga’on on the philosophy of the Hebrew language scream out for translation, printing, and distribution such that they can influence the body politic. It is all well to build the trough, but the horse must know it exists to benefit.

Prescriptivists aren’t attempting to use an inherited language like performance art, but as a regular part of society itself. Classical languages are a continuation–not a clone–of the inherited language. The regular argument against such prescriptivism is that it is an exercise in anachronism: any ‘coined form’ never existed in the language, and therefore cannot be considered a new form. But this reasoning is oversimplified, and misses the goals of linguistic prescriptivism entirely.

To write, speak, and cultivate Classical Hebrew is as much a part of the Classical Hebrew tradition as Miqra itself. We deprive ourselves and our progeny of the opportunity to engage in our true national language, one best suited to divine speech, the language of scripture, and that of the great post-biblical compositions. An ambitious effort appropriate to an ambitious generation.

JT Meghilla 1:9. See also Steiner, R. C. (1992). A Colloquialism in Jer. 5:13 from the Ancestor of Mishnaic Hebrew. Journal of Semitic studies, 37(1), 11-21.

TB Berakhoth 31b, Kethubboth 67b, Sanhedhrin 56a, BM 31b, et al. Used primarily to explain semantically superfluous doubled-verbs, but if true of a particular grammatical feature, then why not the whole language? See also Rabbi Ami’s claim that דברה תורה לשון הואי “the Torah speaks with rhetorical language” in Ḥullin 90b.

Elitzur, Y. (2018). Diachrony in standard biblical Hebrew: the Pentateuch vis-à-vis the prophets/writings. Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages, 44(2), 81-101. Also, Elitzur, Y. (2018). The Interface Between Language and Realia In the Preexilic Books of the Bible. Hebrew Studies, 59(1), 129-147.

Young, I. (2015). “The Greek Loanwords in the Book of Daniel.” In: James K. Aitken and Trevor V. Evans (Eds), Greek Through the Ages: Essays in Honour of John A.L. Lee (Biblical Tools and Studies 22; Leuven: Peeters, 2015), 247–68.

Edrei, A., & Mendels, D. (2014). Why Did Paul Succeed Where the Rabbis Failed? The Reluctance of the Rabbis to Translate Their Teachings into Greek and Latin and the Split Jewish Diaspora. Jesus Research: New Methodologies and Perceptions, 361-397.

See: D. J. A. Clines, The Dictionary of Classical Hebrew, (Sheffield Academic Press, 2011).

M. O. Wise, Language and Literacy in Roman Judaea: A Study of the Bar Kokhba Documents, (Yale University Press, 2015) p. 11.

Wise, Language and Literacy in Roman Judaea: A Study of the Bar Kokhba Documents, p. 11.

R. C. Steiner, “Semitic Names for Utensils in the Demotic Word-List from Tebtunis,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 59, (2000): 191-194.

Steiner, “Semitic Names for Utensils in the Demotic Word-List from Tebtunis,” p. 194.

Bodi, Daniel. (2020). “The Mesopotamian Context of Ezekiel”. In Ezekiel, ed. Corrine Carvalho. Oxford University Press.

See for example, MT, Recitation of Shema`, 2:9.

Morag, S. (1959). Planned and unplanned development in modern Hebrew. Lingua, 8, 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3841(59)90025-7.

Kalev, D. (2010). The Genetic and typological classification of Modern Hebrew: a case study in language profiling. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing. Also see the scholarship of Ghil’ad Zuckermann among others.

For further reading, see Rabin, C. (1983). The national idea and the revival of Hebrew. Studies in Zionism, 4(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13531048308575835

For 100,000, I suggest מְאִיָּה as the kethiv of II Kings 11:4, 19, cognate to Eblaite ma-i-at and Ugaritic miyt ‘hundred thousand’. Rendsburg, G. A. (2002). Eblaite and Some Northwest Semitic Lexical Links. Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, 4, 199-208. For million, I propose חָח from Ancient Egyptian ḥḥ (pronounced *ḥaḥ) ‘one million’. For billion, I propose לִים from Akkadian līm ‘a thousand’. For trillion, I propose עֲנָקָה from Hebrew ע-נ-ק ‘to be giant’ according to the pattern פְעָלָה denominated from רְבָבָה ‘ten thousand’.

Thanks to modern Hebrew doing away with most of the gutteral and dental letters, most Israelis find it difficult to pronounce other languages correctly. The becomes deh, this becomes dis. Think becomes tink. Modern Hebrew is the sound of Eastern Ashkenazim pretending poorly to sound Sephardi. Schools don't teach proper grammar anymore so you get absurdities such as אני יתן. Few Israelis under the age of 40 can pronounce the letter ה correctly. Even in עדות המזרח synagogues, if a youth is called upon to be חזן, you will typically hear everything rushed, garbled, and swallowed. Modern Hebrew isn't just a zombie language, it is a plague. Oh and don't get me started on the brainless habit of filler words in every half sentence even among the elders. Like, you know, say, basically, essentially. כאילו, ת׳יודע, נגיד, פשוט, בעצם. Drives me utterly insane.

You seem to know little about the current debate over how to classify Modern Hebrew, or the permutations other languages underwent. English, for example, changed radically in the wake of the Viking raids, lost its case structure and much else, became radically simplified. Then the Norman invasion took this bare Germanic language and imposed an entire Latinate layer. And that itself underwent centuries of transformation, each generation with its conservatives insisting the language was being defiled. You misunderstand the meaning of language. It serves and reflects the transformations of the people; the people do not serve it.

Ghilad Zuckerman celebrates the hybrid nature of Modern Hebrew, which he calls Yisraelit. So should we. It is indeed a miracle, and the farther it moves from classical Hebrew the more we can see the vitality of the Jewish people.