The Book of the Republic

Devarim as an Outline for Jewish Society

From Vol.1, Issue No. 5 - Sovereignty

By: Jacob Levin

The Constitution of the United States is an awe-inspiring document, in that it was the first in the Western World to delineate the structure, obligations, and boundaries of a government, such that the government would not infringe on the lives of man. However, it is not the first such document outside the West.

The entire book of Devarim functions as a constitution for the Israelite civilization. However, Devarim does not stop at defining a government. It defines the entire republic. The word republic has changed drastically since its coining. Today it refers to a particular system of government. It comes from the Latin res publica, “public thing”, and, as evidenced by the nebulous word “thing”, referred to some amalgamation or abstraction of state and society. In that ancient sense I use the word republic, signified by italics.

The first three parashot, Devarim, Ve’Etchanan, and Ekev, act similarly to the Preamble to the Constitution. They summarize the republic’s purpose: to live in the land of Israel, keeping the commandments to have a relationship with God. The second triad of parashot, Re’eh, Shof’tim, and Ki Tetze, details the government and society of the Israelite republic. The third triad of the book, composed of Ki Tavo, Netzavim, and Vayelekh, describes the fruits of the republic, its implementation, and its transmission. The final two parashot– Ha’azinu, Ve’zot Ha’Berakhah– relate fundamental, illegislable elements: wisdom and character.

As much as I would like to spend a thousand words on each parasha, proving each phrase and clause of my assessment above, I only have a thousand words for all the parashot. So please excuse the hand-waving arguments below; maybe in the future, I can devote an entire article to each parasha, as they deserve.

The parashot of Devarim– the actual breaks in the text, not the weekly portion– are five: (1) An introduction to the book and recounting of the sin of the spies; (2) encountering Esau; (3) encountering Moab; (4) encountering Ammon; and (5) the war against Sihon and Og, and the tribes of Gad and Reuben conquering and settling their territory. The first parasha is about how we rejected the land.1 The middle three parashot are about how the other nations inherited their own land.2 The fifth is that Gad and Reuben are inheriting theirs,3 and now the rest of Israel should inherit theirs, rectifying the sin in the first parasha.

If our goal is to inherit the land, how do we accomplish that? By keeping the commandments.4 Do not stray to idolatry,5 and do not forget your identity.6 Remember always the foundation of our Law,7 and repeat it constantly.8

But do not think that actions alone acquire the land.9 Rather, it is because of a relationship with God,10 for only He grants victory.11

That victory is the usurpation of the land from its previous inhabitants, and is detailed in the second triad. In Re’eh, Moshe instructs that the land should be cleared of evil influence.12 Do not let anyone revert to evil ways.13 Instead, fill the land with good,14 and sacrifice in one place.15

Parashat Shof’tim is filled with laws of government. Establish courts and their officers.16 Establish a High Court,17 and appoint a king.18 When a court can’t administer justice, the king ensures evil is crushed and good prevails.19 He expands the borders of the republic to fill the world with justice.20

Ki Tetze answers the deepest questions about the society of the republic: how we treat each other in difficult, unfortunate situations. How could civilians be enemies, and how do we treat them?21 What a tragedy it would be for a wife to be despised, and how should her husband relate to her? To her son– his son?22 Grapes and wheat were never meant to be together, but here they are: what do we do?23 In an imperfect world, how do we cope? In a world with ‘Amaleq, how do we survive?24

If we follow the laws, implementing the republic as it has been described until this point, we enjoy the fruits of our labor.25 That’s the subject of Ki Tavo. If, however, we do not implement the republic, society collapses. The government fails. Our own brothers treat us with contempt, and we treat God with contempt. Our entire civilization evaporates, and we are exiled, to be ridiculed and defiled.

How important it is then to accept the mandate from God to build this republic. In Netzavim, we are taught that the decision is in our hands, now, to create what God intended us to build.26 The Torah is on Earth27 to actualize its teachings in the form of the republic.

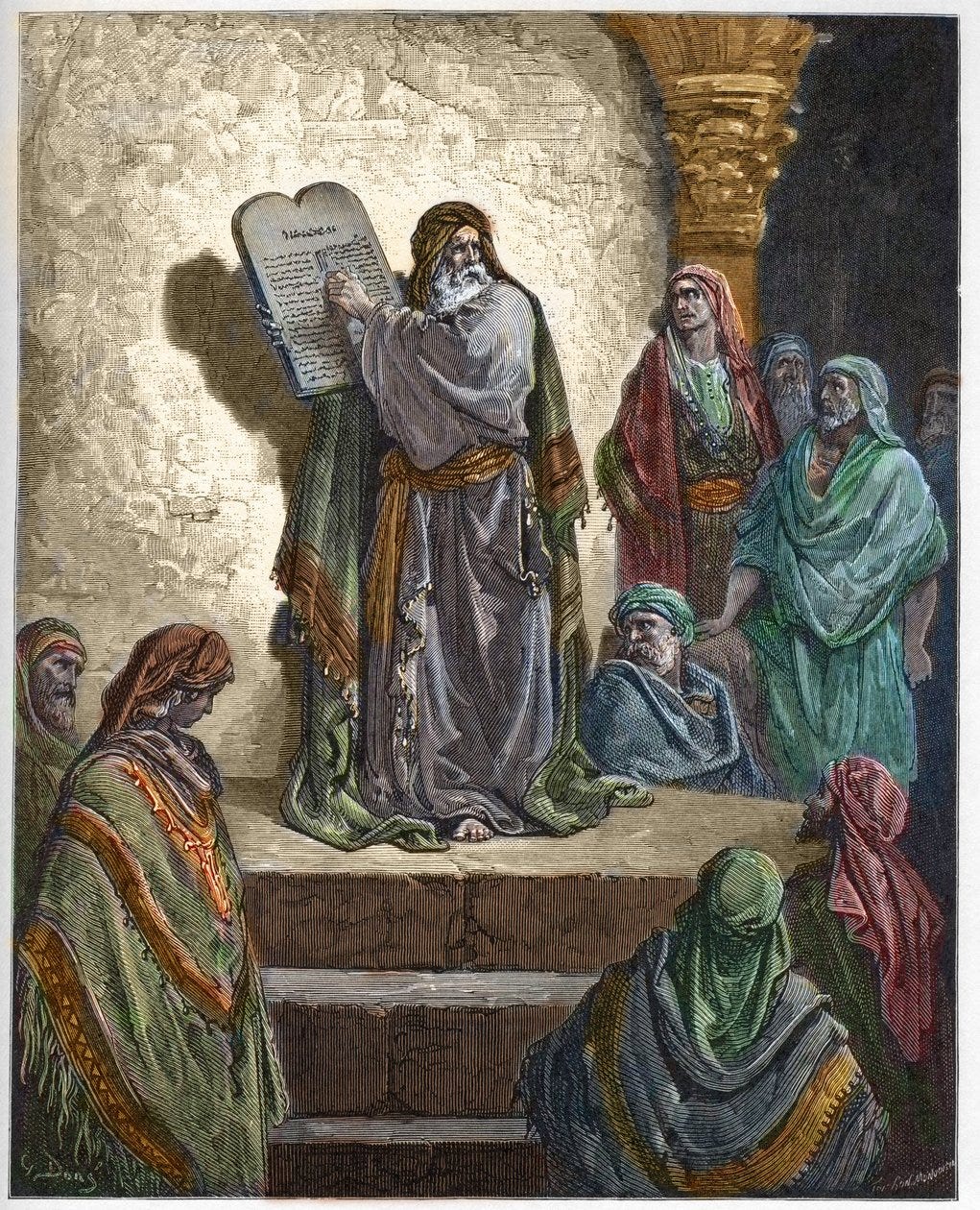

And we must ensure that successive generations will not treat the republic lightly. To instill in our children a love of God, a love of His Torah, and a love of His land. To that end, Moses appoints Joshua, in Parashat Vayelekh. The next generation, our children, must be taught to hold firm to the Torah, to be strong and brave.28 To have a “new Jew” attitude in establishing the republic. Every seven years, the entire nation congregates to study “the Book of the Republic”, even the children– especially the children– so that every generation will be in awe, and hold fast to the good that God gives us in the form of the republic.29

The republic, at this point, would be successfully transferred to the next generation. What more is left?

There are some things that cannot be legislated. The Constitution of the United States did its best, but without the proper “cultural aeroponics” and maintenance, the republic is destined to devolve. One such illegislable thing is wisdom. A wise society rejects the fashions and whims of advertising agencies, preferring the peace produced by sages. Talmidei hachamim, or students of the Sages, generate peace.30 Imagine an entire population of talmidei and talmidot hachamim. Not every member of that society needs the stores of knowledge of a sage; they need only internalize Hillel’s patience and Shammai’s respect.

Wisdom– this is the subject of Ha’azinu. Moses begins his lesson with a praise of God, lauding His justice and morality, directed at the unwise nation that caused destruction.31 The nation has to be told to remember and to receive knowledge from their elders32, two quintessential elements of wisdom and its acquisition. The nation’s beginnings were sweet, but after generations it grew fat and abandoned the trustworthy knowledge of God.33 “They are a nation who destroys good advice, and they themselves have no understanding. If they were wise, they would contemplate this, and understand what their end will be.”34

The final parasha could be understood as federalism, the sharing of political powers between a national government and state or tribal governments. Considering that each tribe is blessed individually, and a king (i.e., a central government) emerges when the tribes unite,35 this reading is entirely valid and plausible. However, such an assessment would make this parasha better suited for the second triad, not the end of the book. Instead, the concept of the parasha is character– tribal identity.

Who today instinctively feels the cultural differences between Connecticut and Rhode Island? Between Delaware and Maryland? Their early histories and cultures were so different, but today, one would be excused for wondering why they are separate states altogether. The same cannot be said for the tribes. Tamar Weissman’s and Fishel Mael’s books, among countless others, are proof of that.

The entire book of Devarim is about the republic, and it seems the final parasha includes a name for that nebulous concept: eshdath, the Fire of the Law.

1:26

2:5; 2:9; 2:12; 2:19; 2:22-23

3:21-22

4:1

4:4

7:3

5:1

6:7

9:5

10:12-16

11:22-23

12:2-4

13:2-19

14:28-15:18

12:5-18

16:18

17:8-13

17:15

Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Melachim uMilhama 3:10

Ibid. 4:10

21:10

21:15-17

22:9

25:17-19

26:1-15; 28:1-14

29:14; 30:15-16

30:12; 30:14

31:6

31:10-13

Talmud Bavli, Berachot 64a

32:2-6

32:7

32:15

32:28-29

33:5