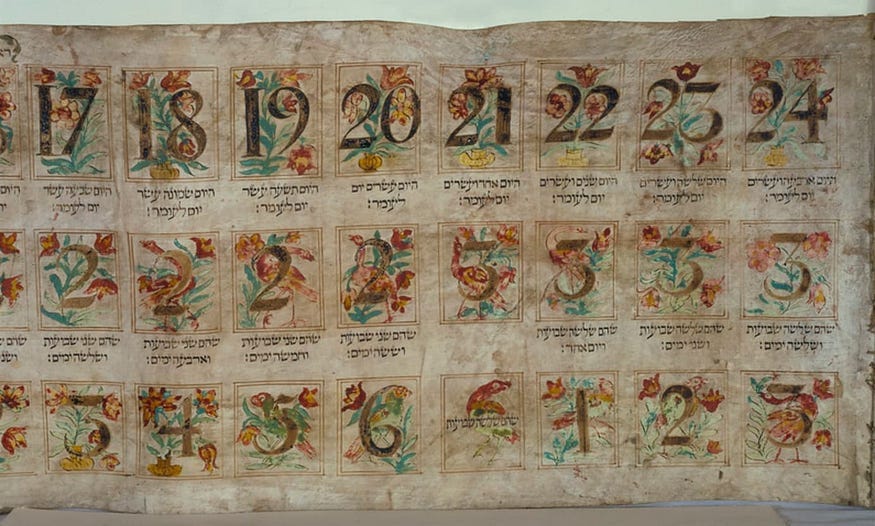

This Month Shall Be For You

Jewish Timekeeping – Its Past, Present, and Future

From Hadesh Vol. 1, Iss. 8 — Calendar

By: Ariel Yaari

The first of the commandments which Hashem commands the Jewish People is to begin calendar-reckoning. Immediately preceding the Korban Pesach, we are commanded thus: “And Hashem said to Moses and to Aaron in the Land of Egypt saying: ‘This month shall be for you head of the months. The first for you out of the months of the year.’”1 As is our wont, the historical enthusiasm to fulfill this commandment has bordered on the extreme and has generated a 3,000-year-long obsession with the calendar and its calculation.

Calendars mark important occasions and events, and adherence to them determines one’s status as either a faithful member of the community or a wanton renegade. This is why some of the most bitter disputes and the most fervent debates in halakha have been over calendrical questions. When splinter Jewish groups wished to separate themselves from the Tradition, the calendar was usually the first thing to be called into dispute. When Jeroboam wished to make a separate cultic center in the north of Israel to rival the south, its Temple, and Biblically-aligned festivals, he delayed the celebration of Sukkot to a month after its traditionally prescribed date.2 Interestingly enough, the Samaritans, the descendants of these northern rebels, continue to celebrate a month after we do.3

Even within the confines of normative Judaism, there can be near schismatic disagreement about the calendar. During the Islamic Golden Age, a dispute emerged between the Geonim of Babylon and the Land of Israel. The Gaon of the Land of Israel, Rabbi Aharon ben Meir, had made some adjustments to the traditionally accepted calculation based on the position of the astronomical bodies over the Land of Israel. He correctly calculated (800 years before the British introduced time zones) that Babylon and the Land of Israel were separated by 8 degrees and 55 minutes longitude.4 This new calculation advanced Pesach two days and began a bloody polemic in the academies of Babylon.5

Similarly, Abraham Ibn Ezra takes up the sword against Rashi’s grandson, Rabbi Shmuel ben Meir (the Rashbam), for having the temerity to suggest that according to the plain meaning of the text, the halakhic day would start at sunrise, and nightfall is a later Rabbinic injunction.6 This was so offensive to the sensibilities of Ibn Ezra that he proceeded to author an entire screed denouncing even a whiff of possibility that this was the simple meaning of the text, and cursing the scribes who would dare copy the words of the Rashbam. If it weren’t for Ibn Ezra, we wouldn’t know of this opinion at all, as the scribes seemed to take his curse quite seriously.

By way of short introduction, I have shown the importance of the calendar and its long and storied role in our history, both in regulating the day-to-day practice of civilizational life and by clearly delineating who is a member of the community. However, its importance isn’t as mere relic or historical curiosity. The communal rhythms of the Jewish People are still dictated by it.

Our perceptive, well-mannered, and incredibly attractive readers will no doubt have noticed that Hadesh does not count the date according to the standard known across the Jewish world. While in English we say the standard name along with the Gregorian year, in Hebrew we always write the month with its Biblical name (e.g. Tishrei – חודש שביעי). This isn’t random or purely aesthetic. Rabbi Yaakov Medan of Gush Etzion has previously lambasted the use of the Babylonian names for the months that we picked up during the First Exile, which are now in common use.7 Just as we wouldn’t (or rather shouldn’t) name a city in Israel after Krakow, Tehran, or New York because Jews had historically lived in those places, would it make any sense for us to persist using Babylonian names because of an Exile that took place 25 centuries ago?

An additional point of curiosity for many is the year we use. All Hadesh issues since we started publication back in Sivan (חודש שלישי) have been dated to the year 77 (ע”ז), instead of the more popular Anno Mundi dating (5786). There also lies an historical reason as to why we date such. During the Bar Kokhba Revolt, the nascent Jewish government began to mint coins that corresponded to the year of the Revolt, e.g. “Year one to the freedom of Israel”, etc.8 This practice lasted as long as the Revolt did. In our own time, with 77 years “to the freedom of Israel”, we find it appropriate to date the year in accordance with the re-establishment of our independence.

As the Jewish People have found themselves reconstituted in their homeland once again, many questions regarding Jewish civilization have emerged. Free of the constraints of Exile, a natural inquisitiveness regarding exactly how to restate our national character has pervaded the thought of many. The obvious subjects such as food, clothing, festivals, and the like have been debated extensively by many. These conversations are good and necessary. However, many other aspects have been neglected, including the very way we tell time.

Beyond the aforementioned point that the calendar serves a vital role in shaping communal boundaries, the way a nation tells its time is directly tied to its self-determination.

Time is precious as we all know, and the one who dictates it dictates the very fabric of reality. At school or work, your time isn’t your own. It belongs either to the headmaster or the boss. You couldn’t very well walk out of work an hour before quitting time. If it happens once, you’d be severely reprimanded. If you had the gall to do it twice, you’d be quickly fired. Your boss dictates the fabric of reality there. From 9-5, you have agreed to give up those precious hours of your day in order to provide labor. Now, eating and being able to afford rent may very well be preferable options over not giving up your time and living on the street.

Outsourcing our time to others means that we are content with a third-party deciding what to do and where to do it. While at a job we receive a check for doing so, when we do so civilizationally, we tacitly admit that we don’t know how to utilize our time properly and that we’d be better off if someone else did it for us. The Hebrew Calendar is currently seen by many as a cute quirk of ours. Today might very well be the 5th of Tevet, but the adults in the room all say December 25th.

Using the Hebrew Calendar seriously is vital to reclaiming ourselves more broadly. However, while it should not be used as an afterthought, it should also not be used to accentuate our “indigeneity” to the Land of Israel. When a culture is powerful, its modes and expressions come naturally. The same way someone says, “The sky is blue”, we should acclimate ourselves to the Hebrew date. Internalized matter-of-factly, not boasted of proudly.

A culture’s power lies in its hegemony, in the unassuming behaviors that people default to subconsciously. When Judaism becomes that for us, we will know that we’re on the right track.

Shemot 12:2

I Melachim 12:32

See Sam Aronow’s excellent video on the subject “The Masoretic Text (750-930)”

Underexplained in the article itself, but the reason this led to such a heated dispute is that according to either opinion, it would result in a large chunk of the Jewish world eating Ḥameṣ on Passover.

Marc B. Shapiro, Changing the Immutable: How Orthodox Judaism Rewrites Its History, (Portland: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2015), pgs. 58-59.

Rabbi Yaakov Medan, “This Month Shall Be For You” - Jewish Dates, (Alon Shevut: Gush Etzion).